More than 2 months have passed since the death of George Floyd. During this time, there have been efforts on an international scale to acknowledge racial injustice and reform systems which allow or encourage racism to persist. In healthcare, data from the CDC has revealed the startling differences between the risk of dying in pregnancy faced by non-Hispanic black women in the United States when compared to all women in pregnancy. More recently, data also from the CDC has shown that two thirds of deaths related to pregnancy were considered to be preventable. In Canada, the story of the preventable death of Brian Sinclair, an Indigenous man who died in a hospital room, shocked the nation in 2008. Despite more than 10 years having passed since his death, there are examples that Indigenous Peoples face inequitable access to healthcare and racism.

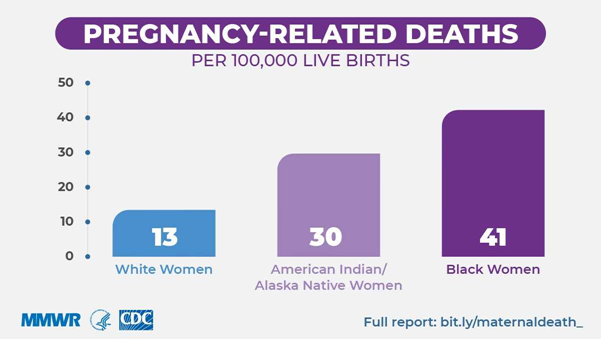

The CDC has recently published data received from 14 Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MMRCs) who were able to review information related to the health and social factors that affect pregnant women. Between 2008 and 2017, information related to the deaths of the 1,347 women who died during pregnancy or within a year of delivery was analysed. These committees found that the deaths could have been prevented in two thirds of the cases. The percentage of deaths that were considered to be preventable did not vary significantly between women of different ethnicities. However, the data published by the CDC in 2019 shows that the risk of dying during pregnancy or within a year of giving birth for non-Hispanic black women was 40.8 per 100,000 births, 29.7 per 100,000 births for non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native women, and overall the mortality rate was 16.7 per 100,000 births.

So why is there a difference in the risk of dying between women of different ethnic backgrounds? Research has shown that the difference may be partly related to medical conditions that ethnic minority women are more vulnerable to. However, this biological basis is less clear as there is also a significant difference in the access to healthcare these women have and the quality of care provided is significantly lower. These differences can influence the impact that any pre-existing medical condition or vulnerability to illness has.

Racial discrimination may also contribute to the severity of the condition. For example, death related to high blood pressure in pregnancy was shown in the research by the CDC to affect proportionally more black women than white women. A study has shown that high blood pressure is more common among those of black ethnicity than white and those who have high blood pressure are more likely to have suffered racism. Therefore, genetic differences may contribute less than discriminatory attitudes and systems.

These inequalities on the basis of race exist internationally. Research looking at maternity care in the U.K. has shown that the rates of death faced by women during pregnancy or in the weeks after birth are five times higher for those of Black ethnic backgrounds and twice as high for those of Asian ethnic backgrounds when compared to white women. Indigenous peoples in New Zealand and Australia face delays in accessing the lifesaving investigation and treatment of heart disease.

The case of Brian Sinclair in 2008 highlighted the issue of healthcare inequality in Canada, where an Indigenous man with cognitive impairment was left without medical care and attention in the waiting room of an ER for 34 hours. An interim report looking into his death, published in 2017, identified that Mr. Sinclair was ignored as a result of racism and lack of care for an Indigenous person. Another report from 2017 reviewed cases in a Saskatoon Health Region hospital where Aboriginal women (this being the way the women described themselves) were coerced into having a surgical sterilization procedure following childbirth. Jordan River Anderson was a First Nations child born with complex medical needs in Manitoba. He spent more than 2 years unnecessarily in hospital awaiting a financial decision about the funding for his home care because he was a First Nations child. He died in hospital without spending a day in his family home.

There are ongoing efforts to address racism in healthcare and physicians in Canada are encouraged to develop their understanding of the barriers faced by those of racial minority groups. There are also physician groups which advocate with and on behalf of affected communities. There are plans to address healthcare inequalities through Jordan’s Principle and the Inuit Child First Initiative.

The extent to which these initiatives lead to significant changes in the provision of healthcare in Canada remains uncertain. What is certain, however, is that healthcare providers are required as a matter of law, to provide all patients with safe and appropriate medical care regardless of the patient’s racial or ethnic background. Moreover, positive steps are required to ensure that equitable treatment and care is received by those of racial minority groups.